If you are not familiar with the Helen Hunt Jackson book or play, you owe it to yourself to make a point of attending the play next year.

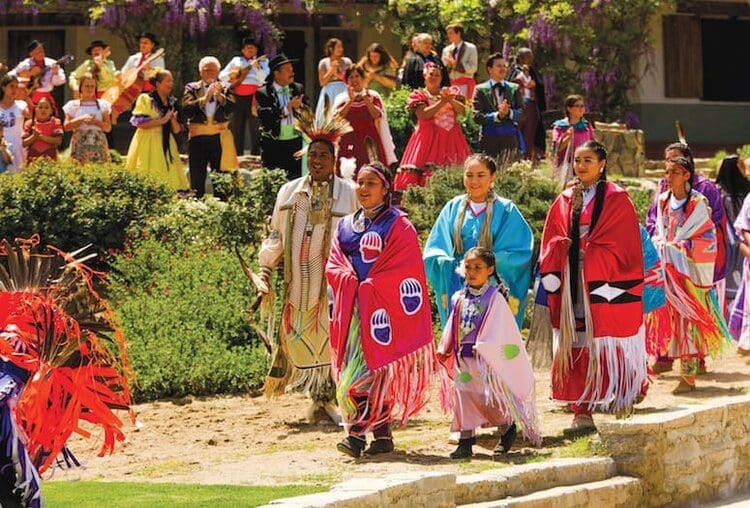

Steve Alvarez with the Red Tail Spirit Singers & Dancers, the Spanish and Heritage dancers and musicians, and |

the Arias Troubadours, who have performed in the play since 1924.

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY RAMONA BOWL

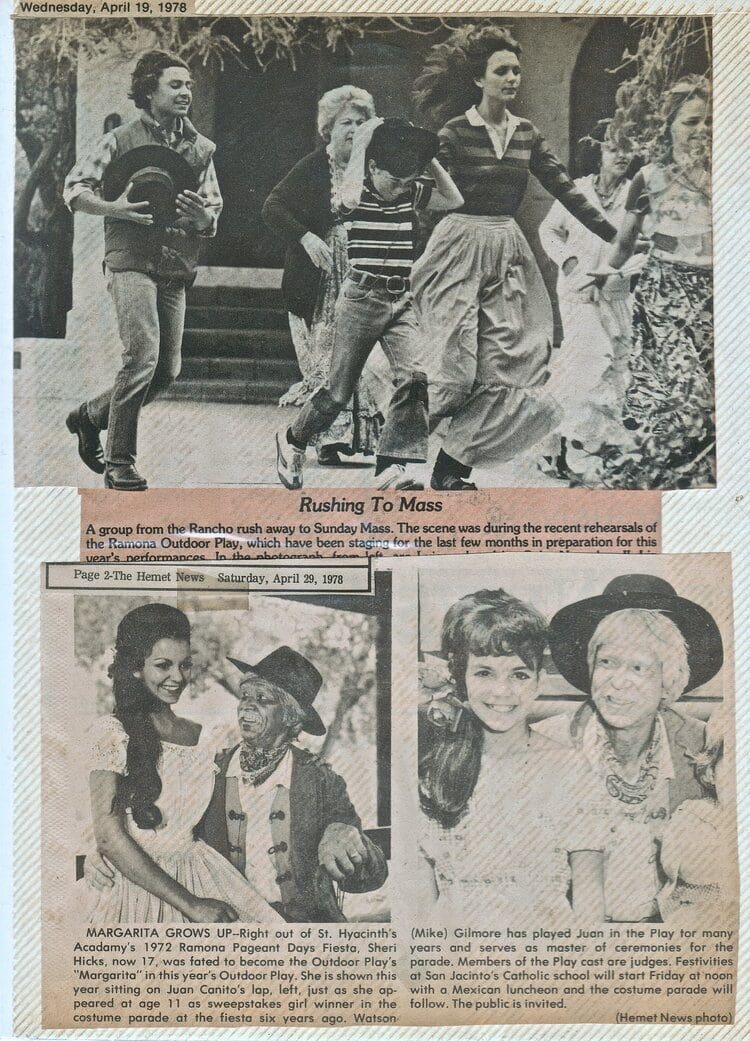

As a native Southern Californian, growing up in Hemet, I had the honor of participating in the play, in one of the lead roles as Margarita, as did my mother before me. Many of my friends played Rock Indians, Spanish Dancers, and other roles. It was as much of our childhood as the miles of orange groves and the intoxicating scent of the blossoms down the hill from the natural outdoor amphitheater.

Editor’s Note: The Ramona Outdoor Play has been canceled for this year due to the COVID-19 virus. This article was written prior to its onset.

Story Courtesy of Kent Black Arts & Entertainment

The Ramona Outdoor Play starts with a bang. A very big bang.

On a several-acre hillside in Hemet, several actors dressed in period Mexican military uniforms of the 1840s detonate a replica 19th-century cannon, marking the first momentous event in this two-plus-hour extravaganza: the handing over of California to the United States by Mexico. (To be clear: There is no cannonball, and the weapon is not aimed at the audience.)

Just as you unclench your buttocks, pull your fingers from your ears, and settle back into your seat in the 5,300-person audience facing the hillside stage, a thundering clatter of horse hooves signals the arrival of two Mexican officers on horseback. Following them are six members of the U.S. Army, led by Kit Carson, who ride in to accept the surrender of the state. Though audience members are sure to take in important details of the natural amphitheater — the corral, multi-room “hacienda,” indigenous dwellings, massive rock outcroppings, crisscrossing trails, and flower gardens around the front of the “set” — it’s difficult to appreciate the scale of the production until people and horses appear, and you realize you’re witnessing an outdoor play, the likes of which have not been seen since the Golden Age of Spanish theater when actual military ships fought in the battle scenes.

“It’s completely unique,” says Dennis Anderson, a retired San Jacinto College theater professor who has been directing the play for the last quarter-century and, as a young man growing up in Hemet, also appeared as an actor. “Part of the draw is experiencing California as it used to be, but the real draw is the experience of outdoor theater. People come here because [there are] cowboys and Indians riding horses, cannons firing, and live music. For years, people have asked us to put it on at night, but we’re purists. Lighting creates an artificial environment and we want to keep the action pure, so the audience can really see Old California.”

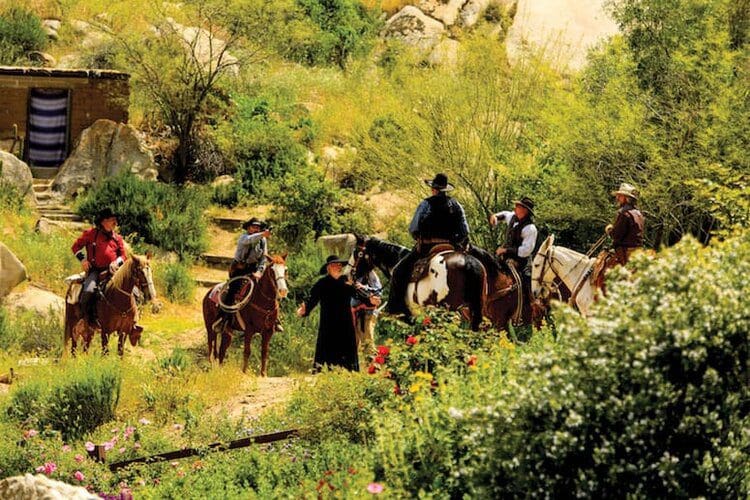

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY RAMONA BOWL

Ramona Cowboys with Padre Gaspara played by Randy Dawkins.

The story is an Old West Romeo and Juliet. Ramona, a half-Native, half-Scottish orphan is the ill-treated, adopted daughter of Señora Moreno, a snobby, prejudiced landowner. Ramona falls in love with Alessandro, the son of the chief of the local Temecula tribe. Dona Moreno condemns their love, and they run away to marry.

The original story was written by Helen Hunt Jackson and published in 1884. Jackson was from the East, wealthy, and well educated. (She was a classmate of Emily Dickinson at Amherst and the two corresponded throughout their lives.) In 1879, Jackson attended a lecture by a Native American chief in Boston who described the exploitation of his tribe by greedy land speculators who forced the removal of his tribe, the Ponca, to Oklahoma, where they lived in poverty and near starvation. Jackson became an activist for Native rights at a time when most European Americans were still reeling from the Battle of Little Bighorn. Undaunted, she enlisted allies among politicians and ministers and tirelessly advocated for the purchase of new and better lands for reservations. On a visit to California, she was told that only a few years earlier, an American wanted some land that was owned by a Soboba Indian in the San Jacinto Mountains above Hemet. His solution was to simply ride to the man’s cabin and shoot him dead. He was never arrested or tried. And he took the land.

Sheri Dettman as Margarita

Hunt returned to New York and wrote Ramona in about three months. Her aim was to write a book that would stir emotions and empathy the way Harriett Beecher Stowe had done with Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Though she died the next year, the book later went through 300 printings and sold more than 600,000 copies, and The North American Review named it one of the most ethical books written in the 19th century.

It may have faded away as another literary curiosity, if not for an unusual theatrical impresario named Garnet Holme. An English emigrant to California in the early 20th century, he was the poor man’s D.W. Griffith, a specialist in outdoor pageants, outsized spectacles with multitudinous casts in natural settings. At the time of his death in Larkspur, Marin County, California, in 1929, he was most well known for staging Drake on Mount Tamalpais. It was an historical reenactment of the English explorer’s arrival on the Northern California coast. However, six years earlier, he adapted Ramona at the behest of the city’s chamber of commerce. Enlisting the town’s populace, he created the Ramona Pageant with a huge cast and a natural amphitheater almost within walking distance of downtown Hemet. Holme’s adaptation was used until playwright and screenwriter Stephen Savage created a new version in 2014. No doubt, Holme would be delighted to know his pageant is the longest-running outdoor play in the United States.

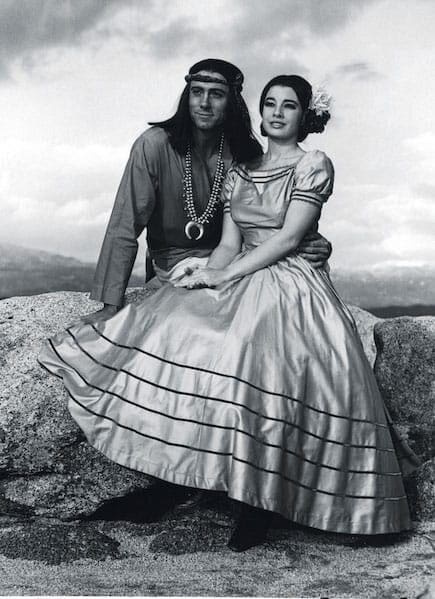

PHOTOGRAPH COURTESY RAMONA BOW

Anne Archer as Ramona and Frank Sorrell as Alessandro.

The pageant used to be an indelible part of growing up in Southern California. For most fourth-graders, field trips were meant to augment their year-long study of California history. There were three principal destinations: The mission of San Juan Capistrano, Olvera Street in downtown Los Angeles, and a performance of Ramona. “We still get the fourth-graders,” says Anderson, who says the Thursday before the opening performance is reserved for fourth-graders from all over Southern California. “The boys go crazy when the cannon goes off or the cowboys ride in, and the girls shout when Ramona and Alessandro first kiss.”

One of the most important parts of Holme’s Ramona legacy was involving the entire community in the production. It was a fairly common practice with 19th century traveling theater troupes to augment productions. The professionals would star in the lead roles while local townspeople would take the roles of spear carriers and ladies in waiting. However, Holme took it a gigantic step further. In the sleepy ranch and farm community of Hemet, he had a robust ethnic mix with which to fill out an Anglo, Hispanic, and Native American cast.

The Ramona Outdoor Play (the former title, The Ramona Pageant, is now more of a nickname) has gone dark only twice: in 1933 during the height of the Depression and 1942 during World War II. It also runs over one of the shortest seasons: six performances on three consecutive weekends from mid-April to early May. It’s actually a huge commitment for a volunteer army. The cast has to be able to commit to nine consecutive weekends of rehearsal before the show’s opening — and that’s not counting costume fittings. Plus, countless volunteers run the concessions and parking lot. “Without our volunteers,” Anderson says, “we’d be done.”

Read more here about the play, including cast members Raquel Welsh and Anne Archer…